PicoCTF WebNet1

In this write-up for the picoCTF challenge "WebNet1", we decrypt TLS traffic using a provided private key. Follow along as we use Wireshark to extract decrypted HTTP files and uncover the flag through analysis.

In this write-up, we’ll delve into the picoCTF challenge “Investigative Reversing 0,” which is categorized as a medium-level forensics challenge. The challenge description:

“We have recovered a binary and an image. See what you can make of it. There should be a flag somewhere.”

Upon downloading the challenge files, we are presented with two files: mystery (a binary file) and mystery.png (an image file). Let’s explore these files to uncover the hidden flag.

To start our investigation, we’ll use the file command on each of the provided files to gain insight into their formats and types. This preliminary step will help us understand what we’re dealing with before diving deeper into the analysis.

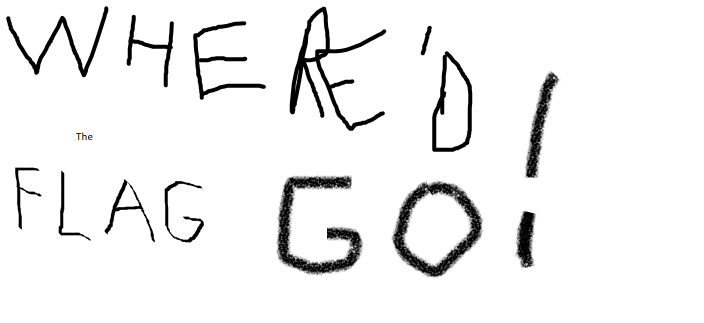

mystery.png: PNG image data, 1411 x 648, 8-bit/color RGB, non-interlaced

Opening up the PNG we are presented with:

mystery: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, BuildID[sha1]=34b772a4f30594e2f30ac431c72667c3e10fa3e9, not stripped

Next, we’ll open the binary in IDA Pro and disassemble the program. Upon loading the binary, we’ll examine the main function. The program is relatively small, and within the main function, we observe that it attempts to open a file named flag.txt for reading. Additionally, the program tries to open mystery.png—the image file we downloaded—for appending.

Tech Tip: When working with library calls like fopen(), it’s useful to refer to the man pages in Linux to understand the arguments and return values. For example, you can use the command $ man fopen to access detailed documentation about the fopen function.

int __fastcall main(int argc, const char **argv, const char **envp)

{

v10 = __readfsqword(0x28u);

stream = fopen("flag.txt", "r");

v8 = fopen("mystery.png", "a");

if ( !stream )

puts("No flag found, please make sure this is run on the server");

if ( !v8 )

puts("mystery.png is missing, please run this on the server");

if ( (int)fread(ptr, 0x1AuLL, 1uLL, stream) <= 0 )

exit(0);

puts("at insert");

fputc(ptr[0], v8);

fputc(ptr[1], v8);

fputc(ptr[2], v8);

fputc(ptr[3], v8);

fputc(ptr[4], v8);

fputc(ptr[5], v8);

for ( i = 6; i <= 14; ++i )

fputc((char)(ptr[i] + 5), v8);

fputc((char)(ptr[15] - 3), v8);

for ( j = 16; j <= 25; ++j )

fputc(ptr[j], v8);

fclose(v8);

fclose(stream);

return __readfsqword(0x28u) ^ v10;

}

If either of the fopen() function calls fails or returns an invalid handle, the program prints an error message and then attempts to call fread(). If fread() also encounters an error, the program will exit.

To proceed, let’s start by creating a flag.txt file in the current directory to ensure the program can access it.

touch flag.txt

Lets now look at the man page for fread().

size_t fread(void *ptr, size_t size, size_t nmemb, FILE *stream);

DESCRIPTION

The function fread() reads nmemb items of data, each size bytes long, from the stream pointed to by stream, storing them at the location given by ptr.

In our case, ptr refers to the location where we are storing the read data, and the stream is flag.txt, from which we are reading 26 bytes (0x1A in hexadecimal). Additionally, v8 is the file pointer for mystery.png. To enhance clarity in our analysis, let’s rename the variables to something more descriptive.

fp_flag = fopen("flag.txt", "r");

mystery_img = fopen("mystery.png", "a");

if ( !fp_flag )

puts("No flag found, please make sure this is run on the server");

if ( !mystery_img )

puts("mystery.png is missing, please run this on the server");

if ( (int)fread(flag_data, 0x1AuLL, 1uLL, fp_flag) <= 0 )

exit(0);

puts("at insert");

fputc(flag_data[0], mystery_img);

fputc(flag_data[1], mystery_img);

fputc(flag_data[2], mystery_img);

fputc(flag_data[3], mystery_img);

fputc(flag_data[4], mystery_img);

fputc(flag_data[5], mystery_img);

for ( i = 6; i <= 14; ++i )

fputc((char)(flag_data[i] + 5), mystery_img);

fputc((char)(flag_data[15] - 3), mystery_img);

for ( j = 16; j <= 25; ++j )

fputc(flag_data[j], mystery_img);

fclose(mystery_img);

fclose(fp_flag);

return __readfsqword(0x28u) ^ v10;

The code writes the first 6 bytes of flag_data directly to mystery.png. It then increments the next 9 bytes by 5 before writing them, decrements the 16th byte by 3, and writes the remaining bytes as-is. After writing all the data, the program closes both files.

To test this, we’ll start by populating flag.txt with 26 ‘a’ characters. Next, we’ll create a backup of mystery.png to compare the file before and after the modifications. By examining the hexdump of both versions, we can observe the changes made by the program.

aj@ubuntu ir0 % hexdump -C mystery.png.bak | tail

0001e800 08 82 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 08 42 f6 21 23 11 82 |.. .. .. .B.!#..|

0001e810 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 64 1f 32 12 21 08 | .. .. .. d.2.!.|

0001e820 82 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 08 42 f6 21 23 11 82 20 |. .. .. .B.!#.. |

0001e830 08 82 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 64 1f 32 12 21 08 82 |.. .. .. d.2.!..|

0001e840 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 08 42 f6 21 23 11 82 20 08 | .. .. .B.!#.. .|

0001e850 82 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 64 17 ff ef ff fd 7f 5e |. .. .. d......^|

0001e860 ed 5a 9d 38 d0 1f 56 00 00 00 00 49 45 4e 44 ae |.Z.8..V....IEND.|

0001e870 42 60 82 70 69 63 6f 43 54 4b 80 6b 35 7a 73 69 |B`.picoCTK.k5zsi|

0001e880 64 36 71 5f 66 62 35 31 63 38 32 31 7d |d6q_fb51c821}|

0001e88d

aj@ubuntu ir0 % ./mystery

at insert

aj@ubuntu ir0 % hexdump -C mystery.png | tail

0001e820 82 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 08 42 f6 21 23 11 82 20 |. .. .. .B.!#.. |

0001e830 08 82 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 64 1f 32 12 21 08 82 |.. .. .. d.2.!..|

0001e840 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 08 42 f6 21 23 11 82 20 08 | .. .. .B.!#.. .|

0001e850 82 20 08 82 20 08 82 20 64 17 ff ef ff fd 7f 5e |. .. .. d......^|

0001e860 ed 5a 9d 38 d0 1f 56 00 00 00 00 49 45 4e 44 ae |.Z.8..V....IEND.|

0001e870 42 60 82 70 69 63 6f 43 54 4b 80 6b 35 7a 73 69 |B`.picoCTK.k5zsi|

0001e880 64 36 71 5f 66 62 35 31 63 38 32 31 7d 61 61 61 |d6q_fb51c821}aaa|

0001e890 61 61 61 66 66 66 66 66 66 66 66 66 5e 61 61 61 |aaafffffffff^aaa|

0001e8a0 61 61 61 61 61 61 61 |aaaaaaa|

0001e8a7

An interesting observation is that towards the bottom of the file, there is an ASCII printable string that resembles the flag. It appears that our flag data has been transformed and appended to the end of the file as we expected. Given this, it’s plausible that the same transformation applied to the flag data could have been used on the flag-like strings found at the bottom of the file. To uncover the original flag, we can apply the reverse of the transformation process to the data using the inverse of the logic used during modification.

picoCTK.k5zsid6q_fb51c821}

aaaaaafffffffff^aaaaaaaaaa

To recover the original flag data, you can either manually decode it using an ASCII table or automate the process with a Python script. Both approaches offer valuable insights and learning experiences. Below is a Python script that reverses the transformation applied to the flag data:

def reverse_bytes(raw_bytes):

# Reconstruct the original flag_data as a list of integers

original_flag = [0] * 26

# Directly copy bytes 0-5

original_flag[0:6] = raw_bytes[0:6]

# Reverse the modification for bytes 6-14 by subtracting 5

original_flag[6:15] = [b - 5 for b in raw_bytes[6:15]]

# Reverse the modification for byte 15 by adding 3

original_flag[15] = raw_bytes[15] + 3

# Directly copy bytes 16-25

original_flag[16:26] = raw_bytes[16:26]

# Convert the list of bytes to a string

return bytearray(original_flag).decode('utf-8')

# Given raw bytes

raw_bytes = [

0x70, 0x69, 0x63, 0x6f, 0x43, 0x54, 0x4b, 0x80, 0x6b, 0x35,

0x7a, 0x73, 0x69, 0x64, 0x36, 0x71, 0x5f, 0x66, 0x62, 0x35,

0x31, 0x63, 0x38, 0x32, 0x31, 0x7d

]

# Reverse the processing to get the original flag_data

original_flag = reverse_bytes(raw_bytes)

print("Original Flag Data:", original_flag)

Flag: picoCTF{f0und_1t_fb51c821}