Introduction

This is a write-up for the picoCTF challenge “Droids 4”. Classified as a hard reverse engineering task, the description prompts: “Reverse the pass, patch the file, get the flag.” In this blog post, I will demonstrate an alternative approach that deviates from the common solution.

Write-up

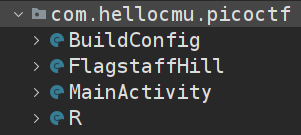

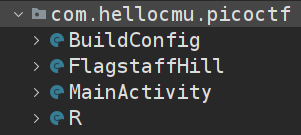

Upon downloading the file, we receive ‘four.apk.’ My go-to tool for inspecting APK or Java files is Jadx. At first glance, we see several classes.

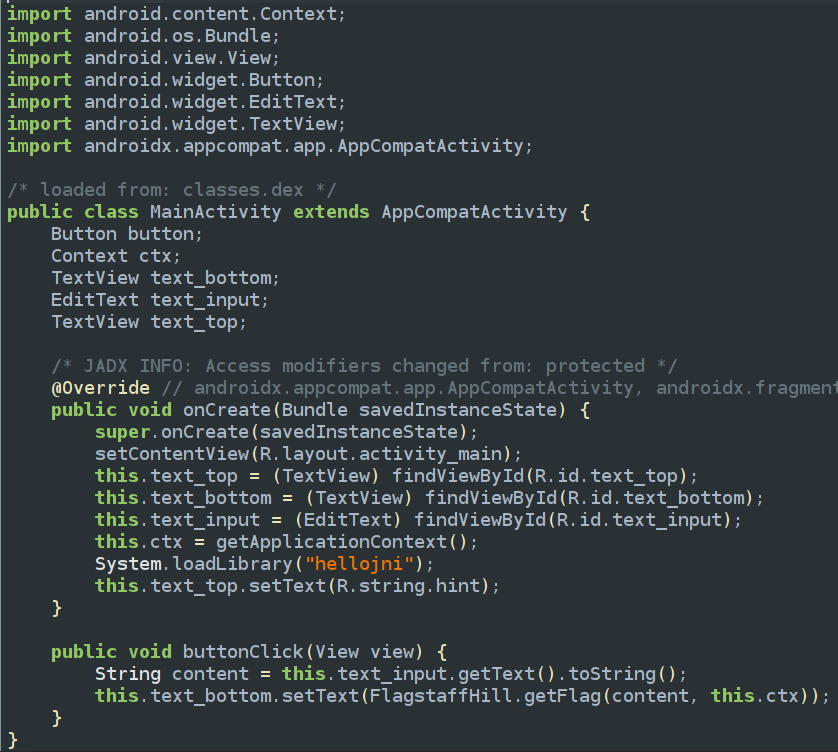

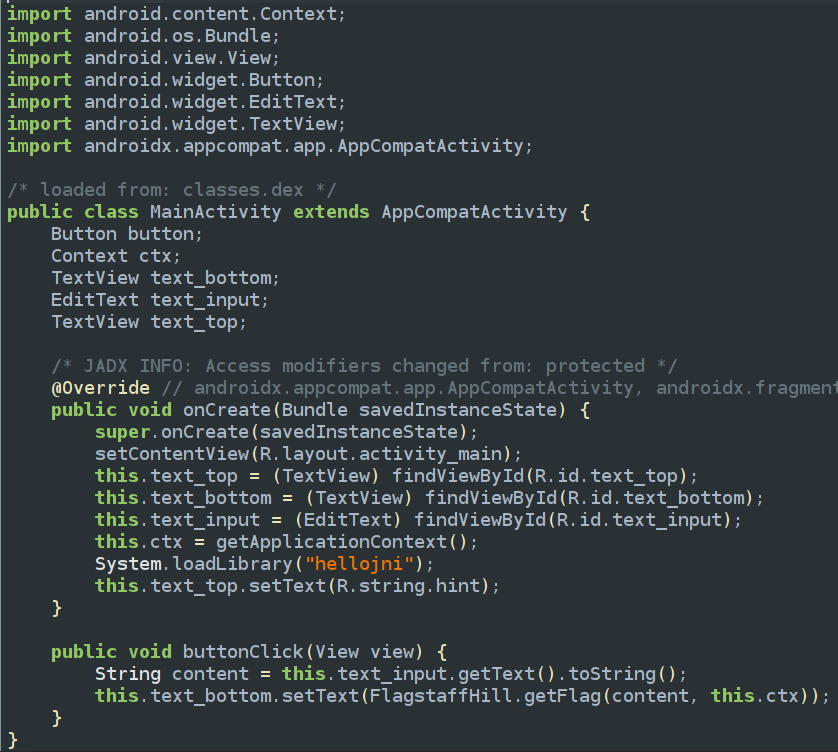

The MainActivity class is relatively straightforward, involving buttons, text, and a hint string. When the button is clicked, it retrieves the input text and passes it to the getFlag() function, which then displays the returned value of getFlag() on the screen.

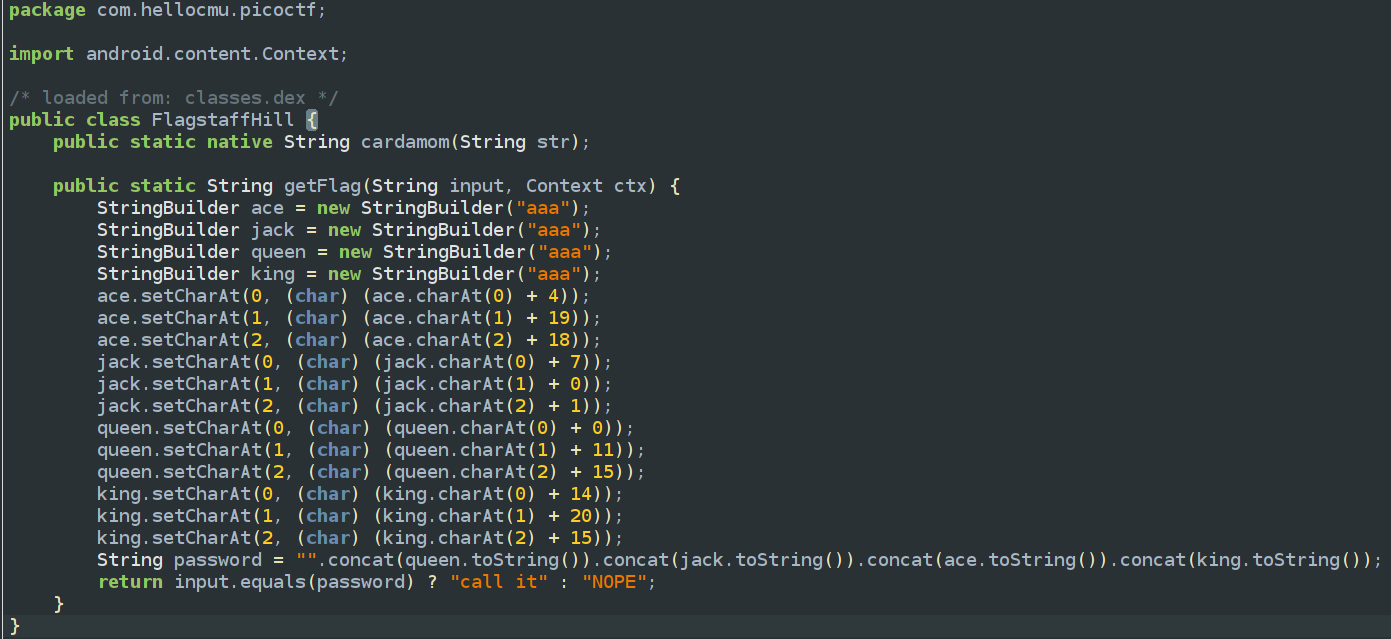

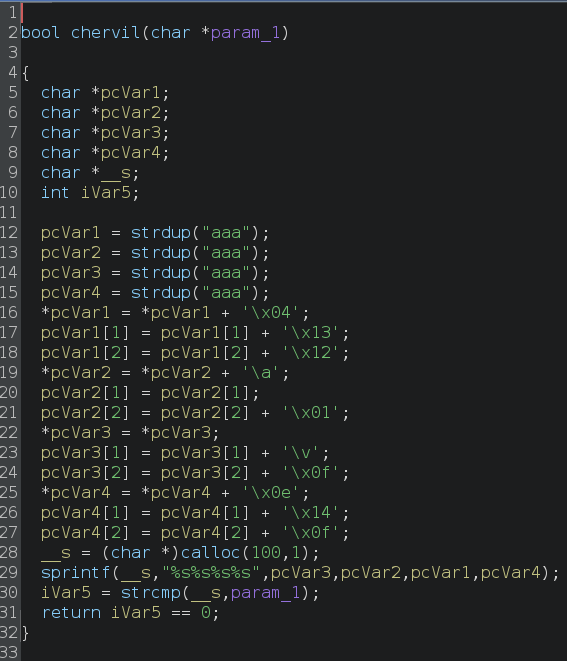

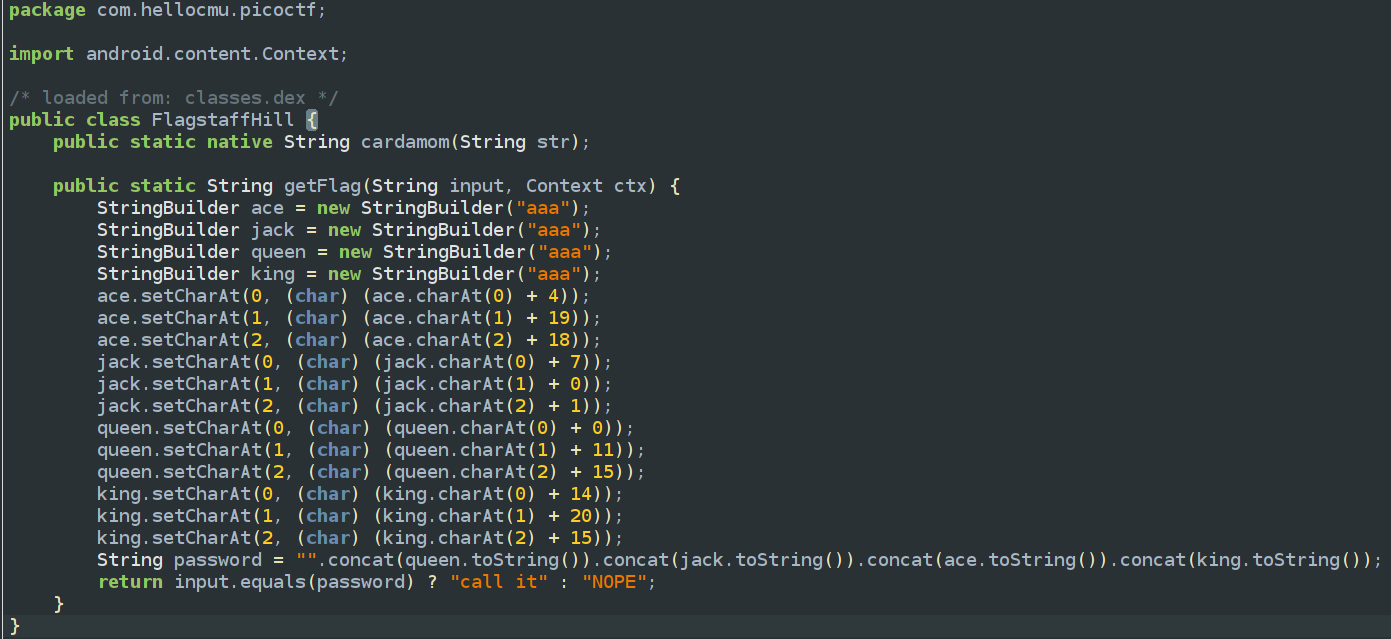

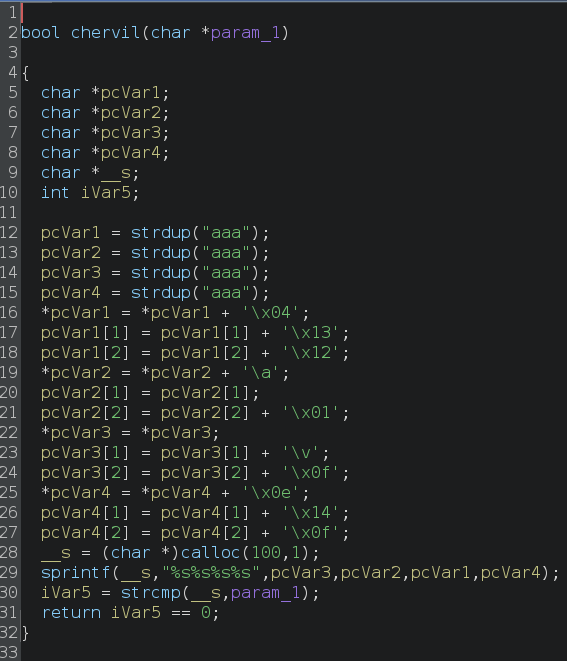

In the FlagstaffHill class, the getFlag() function constructs a password by transforming and concatenating four strings (queen, jack, ace, king) into “alp,” “hab,” “ets,” and “oup,” respectively, forming the final password “alphabetsoup.” This password must match the user input to return “call it”; otherwise, it returns “NOPE.”

So, entering “alphabetsoup” should reveal the flag, right? Not exactly. It merely returns that string, and the MainActivity class sets this value as text. The challenge’s hint, “call it,” led me to explore the function “cardamom()” in FlagstaffHill().

Alternate path

In this situation, many, including myself, would patch the Java class to call cardamom() with “alphabetsoup” as the parameter, which indeed yields the flag. While this does give you the flag, it drove me crazy because I wanted to understand why the “public static native String cardamom()” function is so secretive. What is the cardamom() function doing that allows us to get the flag?

In Jadx, you can’t simply click on the function to see the code being executed. We’ll figure out why that is in a moment. Also, who really enjoys signing APKs and dealing with Android Studio 😅? Let’s find out what this function does.

A bit of googling around for what the native in ‘public static native’ represents resulted in some interesting findings:

Simply put, this is a non-access modifier that is used to access methods implemented in a language other than Java like C/C++.

https://www.baeldung.com/java-native

Interesting, this function must be written in C or C++ and compiled, then added into this java program. This makes sense why Jadx isn’t able to view it because it is a Java decompiler and doesn’t have the capability of disassembling and viewing binary opcodes.

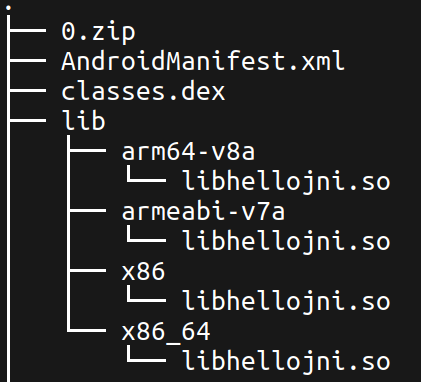

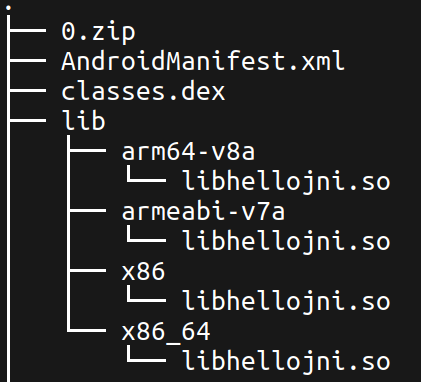

Let’s use Binwalk to extract all files. Binwalk successfully extracts various directories, including ./lib, which houses binaries for different architectures.

I’ll use “/lib/x86/libhellojni.so” to avoid the headache of ARM assembly 😂

libhellojni.so: ELF 32-bit LSB shared object, Intel 80386, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, BuildID[sha1]=0b26bd0857c9b78695535273c86549b2c3da8512, stripped

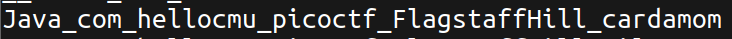

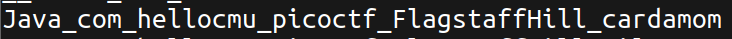

Running strings on the binary reveals an interesting ASCII string, our cardamom function declaration! Let’s disassemble this binary using Ghidra.

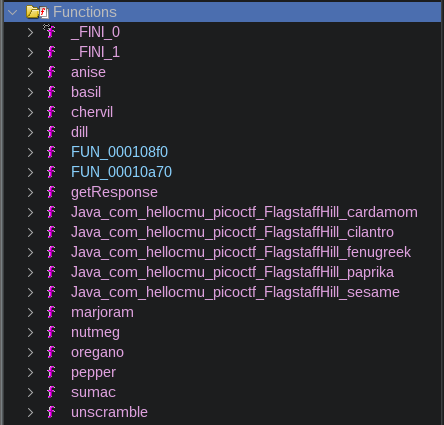

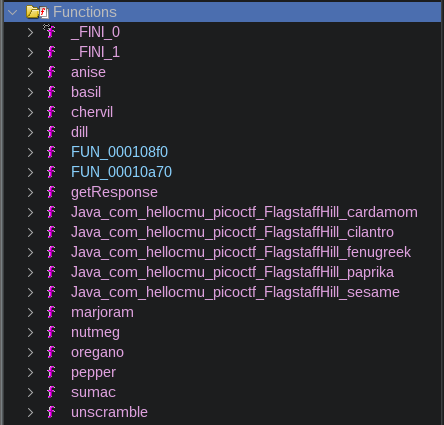

The function list shows our function of interest, “cardamom”, and funny enough maybe some other functions that were used for past challenges. Alright lets navigate to “cardamom” function.

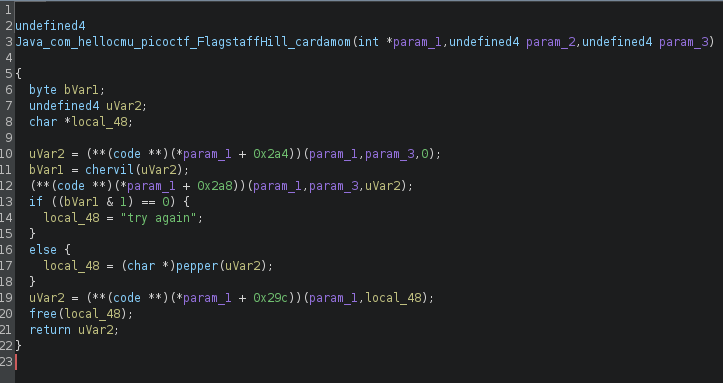

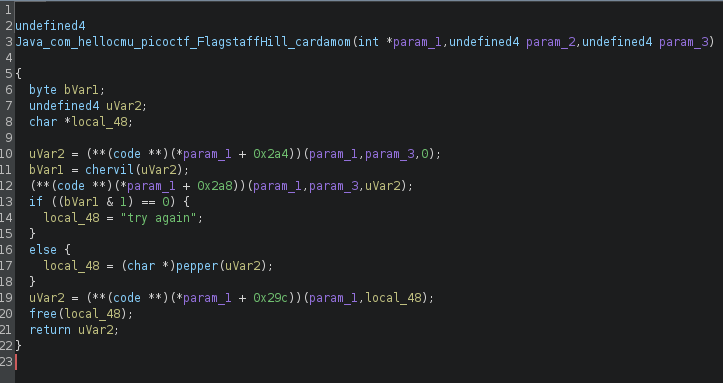

Awesome!! Not so secretive after all.

uVar2 appears to be our user input, which needs to be “alphabetsoup.” The function calls chervil(uVar2), this function is identical to the getFlag() that was in the Java APK.

Continuing in the cardamom function, if chervil() returns valid, we call pepper().

This is so much fun 🙂

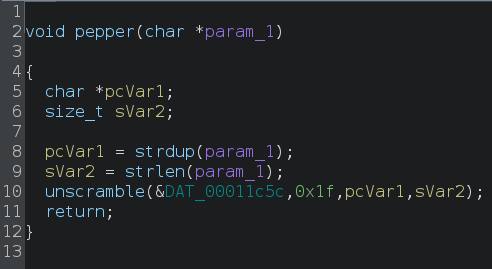

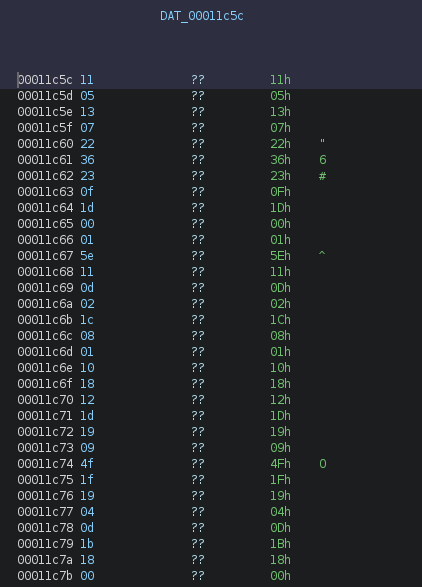

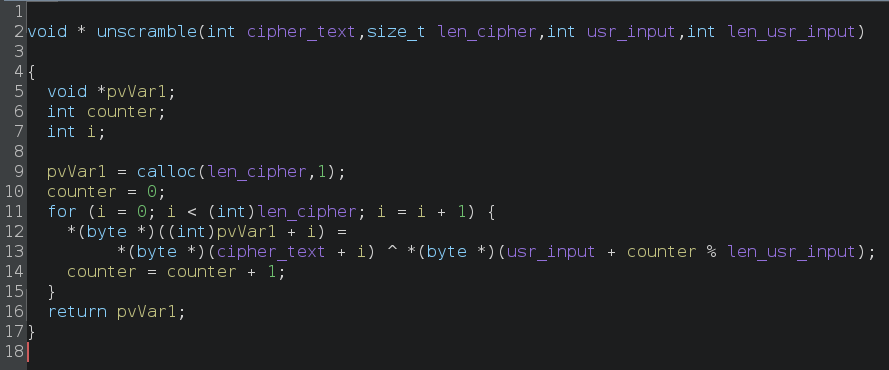

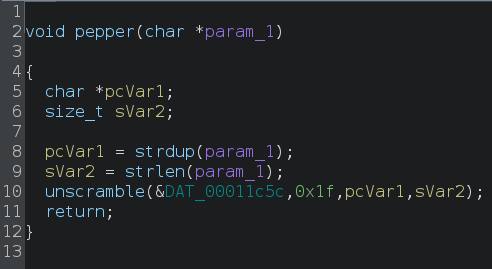

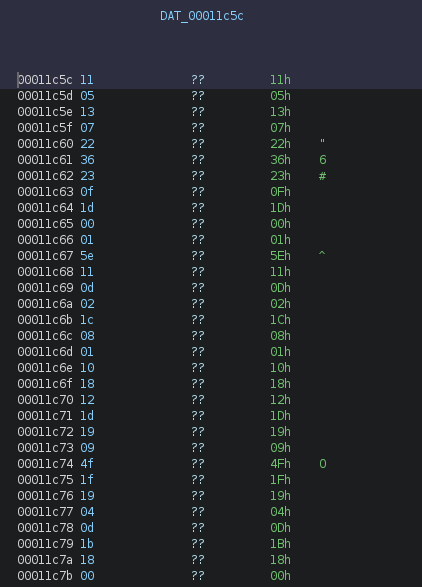

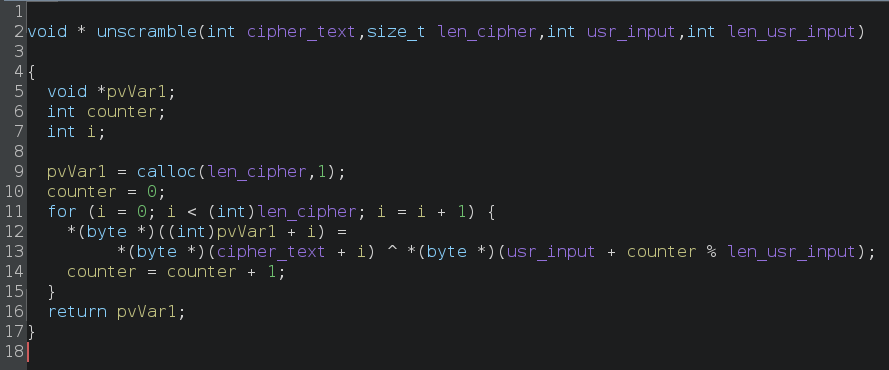

Lines 8 and 9 call common C library functions, strdup (duplicates a string) and strlen (calculates the length of a string). We then reach the unscramble() function, which takes four parameters: DAT_00011c5c (a pointer to a byte sequence in the data section), 0x1f (the length of DAT_00011c5c), the duplicated user input, and its length.

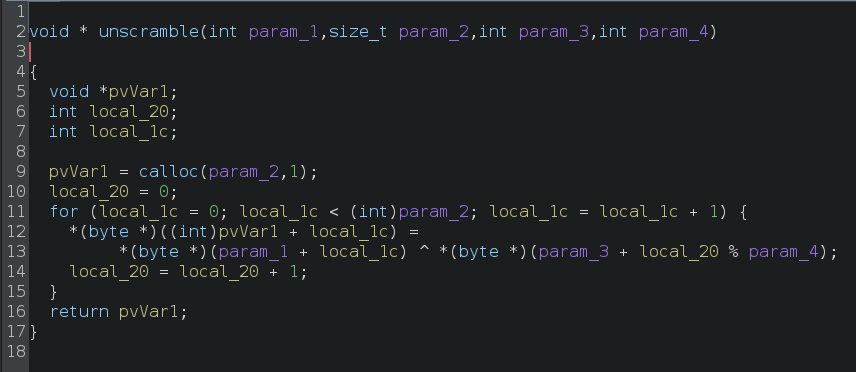

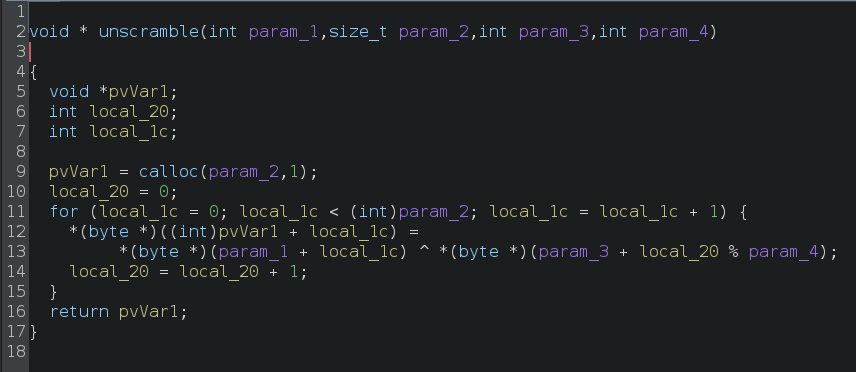

The unscramble() function performs a simple XOR decryption.

Lets rename some of the variables to make this easier to read.

After renaming variables, we can now write a Python script to decrypt this data.

def unscramble(cipher_text, usr_input):

len_cipher = len(cipher_text)

len_usr_input = len(usr_input)

pvVar1 = bytearray(len_cipher)

counter = 0

for i in range(len_cipher):

pvVar1[i] = cipher_text[i] ^ usr_input[counter % len_usr_input]

counter += 1

return bytes(pvVar1)

# Given parameters

cipher_text = b'\x11\x05\x13\x07\x22\x36\x23\x0f\x1d\x00\x01\x5e\x11\x0d\x02\x1c\x08\x01\x10\x18\x12\x1d\x19\x09\x4f\x1f\x19\x04\x0d\x1b\x18\x00'

usr_input = b"alphabetsoup"

# Unscramble the cipher text

decoded_text = unscramble(cipher_text, usr_input)

print(decoded_text)

Running the script reveals our flag!

Flag: picoCTF{not.particularly.silly}

Conclusion

This challenge, while intended to be solved by patching the Java class and running the modified APK in Android Studio or an emulator, provided an intriguing alternative path. By discovering the native keyword in the function declaration, we realized that the function was implemented in C/C++. We then extracted the files to locate the binary that housed the native code. Disassembling this binary with Ghidra allowed us to understand the underlying mechanics. Ultimately, we wrote a Python script to decrypt the data, revealing the flag. This approach highlights the importance of exploring various angles in reverse engineering to fully comprehend the complexities of a challenge. Remarkably, the entire process was accomplished statically, without needing to emulate or run the binary, underscoring the power of thorough static analysis in uncovering intricate details.

-Aaron